Sustaining Life with Pearl Farming

From the April 2021 issue of #thisispearl digital magazine

One of the most important aspects of pearl farming is the ability to protect and create more life than what was available previously. What do I mean by this? When you start a pearl farm, you begin with a resource that has already been “pillaged and plundered” for probably hundreds, if not thousands, of years. As an example, we have the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf, whose pearls adorned the ancient rulers of Egypt, Persia, and Rome. Or the more recent Gulf of California pearl fisheries that began an intense fishery in the 1600s. What we see today is just a shadow of what existed before the California fisheries started some 420 years ago.

When you start a pearl farm, you will commence on a previously fished and impacted environment, where pearl oysters are usually not abundant. This was very much the scenario I encountered back in 1992 in Bacochibampo Bay, Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico; I conducted a mollusk census that revealed that in an area of 400 hectares (988 acres), fewer than 150 live pearl oysters existed. This means that there were just 0.355 oysters per square meter (/m2). Why should we care about this? Because pearl oysters are sessile and cannot move about to go on dates with others, so they need to live in clusters or pearl beds, or else they cannot successfully breed. According to studies, you need at least 10 oysters per square meter to ensure successful reproduction, and the chances of the microscopically small sexual cells finding each other diminishes dramatically with fewer oysters.

In the above example, Sea of Cortez pearl oysters were on the brink of a local extinction event, just about ready to disappear, until a small research group (me and some friends) put a stop to it by gathering as many of the wild oysters as we could, then placing them together in a protective cage in the bay. They started breeding in captivity, but their descendants were free to head out to sea. At 150 oysters per square meter, they were at least 14 times more successful than the minimum number required, and many times more successful than dispersed all over the bay. And then, slowly, “biological magic” began to happen. Stay tuned to learn more in the June edition of #thisispearl!

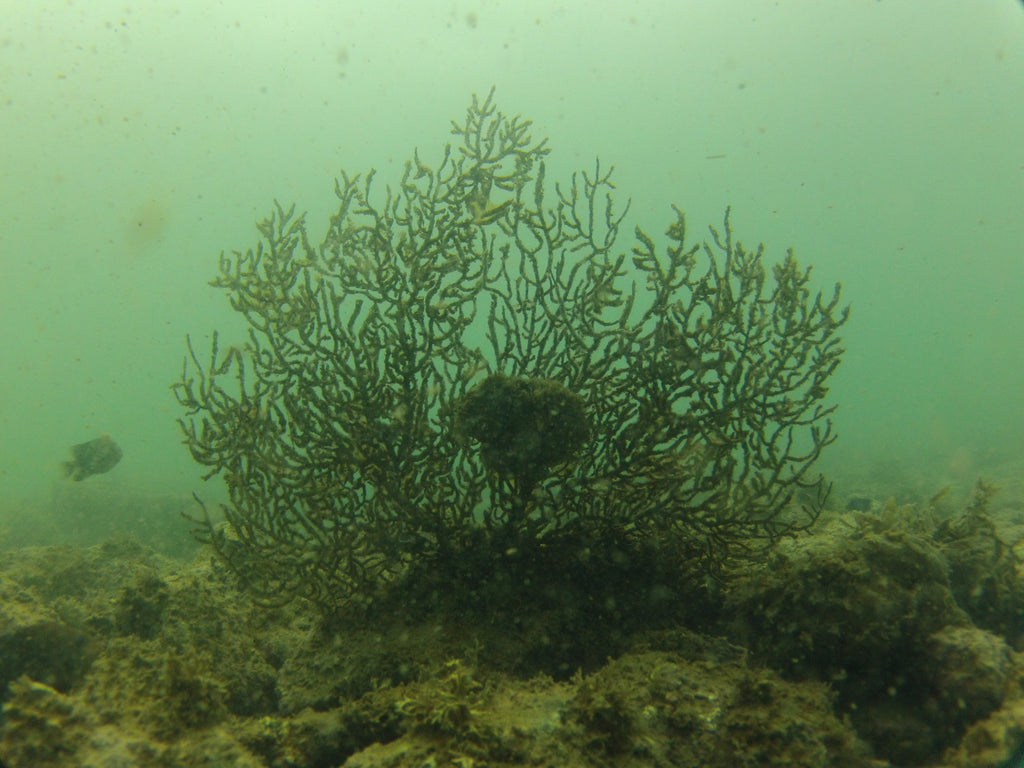

Douglas McLaurin-Moreno is a biochemistry engineer with a master’s degree in sustainability and natural resources management as well as a university professor, PAO instrstructor, and a founder of the Sea of Cortez pearl brand, the first commercial marine pearl farm in the entire American continent. Image is Moreno's own, Pteria sterna on fan coral in the Sea of Cortez

Comments on this post (0)